13 Nov Talking with Alice Gu: Why The Donut King is the American Story We Need

BY DIANA LU

cinéSPEAK is proud to be an official PAAFF 2020 Community Partner.

The Donut King is the closing night film at the 2020 Philadelphia Asian American Film Festival, where it will be screening live on November 15, at 6:30pm. The film is followed by a Q+A with Alice Gu. Purchase tickets here.

**Use this promo code at checkout to get $2 off your ticket: DONUTROYALTY**

There are 5,000 independently owned donut shops in Southern California; roughly 90 percent are owned by Cambodian-Americans. How did this happen?

In her new documentary The Donut King, director Alice Gu takes us through the rise, fall, and redemption of Ted Ngoy, a Cambodian refugee turned successful businessman who sponsored hundreds of visas for fellow refugees and built an unexpected empire that forever changed American food culture.

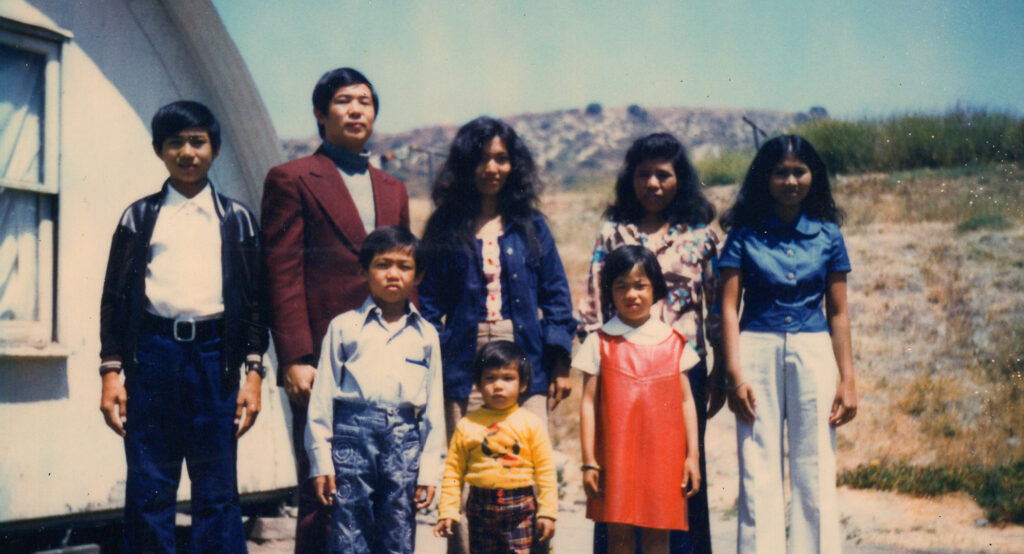

In 1975, the Khmer Rouge were closing in on Phnom Penh, Cambodia’s capital. Bun Tek ‘Ted’ Ngoy and his family fled the Cambodian genocide and landed in Camp Pendleton in California. In just a few short years, Ted would become a multi-millionaire and respected figure in the business community and Republican party (he has met three U.S. presidents). He would help hundreds of Cambodian refugees start new lives and build a network of thousands of independently-owned donut shops. He would lose it all—his fortune, his family, and his reputation—to gambling. This story has all the elements of the rags-to-riches stories we love, with the tantalizing backdrop of fried desserts, to rope in film nerds, history buffs, and foodies alike.

I had the opportunity to speak with Alice Gu about how the political climate motivated her to tell this refugee success story, directing her first feature-length film, and why Cambodian donuts made her believe in America again.

Gu tells me that since the release of the film, she’s been getting DMs and emails from strangers; “They were like: This was so nice to see, right before the election, especially, I got super emotional, this made me feel a bit better about America,” she explains. The film struck me similarly. It felt triumphant in being both so American and so pro-immigrant, when people tend to use those terms like they aren’t one and the same.

Making this film, Gu had never felt more patriotic. “I’ve never been proud of this country and proud of Americans,” Gu tells me. “This is the country that let my parents in. I talked to my mom, who said that America was the country that everyone was clamoring to get to.”

“Everyone was so nice,’” her mom told her. “‘You didn’t have to lock your doors!’”

This idyllic, welcoming society reminded me of how my mother, a Vietnamese refugee, described the excitement of her first American meal, after she landed in the San Gabriel Valley in California. It was a hamburger from The Hat, an iconic local pastrami sandwich chain. “I thought, my god, it was so delicious, more delicious than anything I had ever eaten before,” my mother told me. That taste of freedom is why eating at The Hat was such a treat for my mom. I see that same feeling of freedom in Ted’s smile when he eats a donut.

The Donut King shows audiences how Ted learned the tricks of the trade through Winchell’s manager training program. Back then, the donut giants had carved out territory—Dunkin’ Donuts had the East Coast, Krispy Kreme had the South, and Winchell’s had the West. Winchell’s training and franchise model taught budding entrepreneurs everything they needed to know to run a successful donut shop—baking, payroll, staffing—and achieve the American dream. Ted managed a Winchell’s branch and saved enough to buy his first shop, Christy’s Donuts, a year later. When it came time for his wife Suganthini to choose her English name, she became Christy.

At the peak of his success, Ted owned about 65 donut stores and an estimated wealth of $20 million. Gu shows us the opulence with a copious photo montage of parties, boats, furs, perms, fast cars, a 50-person dance troupe, world travel, all set to swanky Charlie’s Angels-esque music.

One of his mentees bought a distribution company and they supplied the shops with all the ingredients and boxes. The model—and community—sustained itself, at a rate of 100 new Cambodian shops a month. They ate up the competition. “One of the struggles we had—we would train them, and when they had enough money, they would quit and compete with us,”’ says the former CEO of Winchell’s with a laugh. They drove Dunkin’ Donuts out of the West Coast.

Gu grew up in the South Bay, not far from me, it turns out, but worlds away culturally. We are both ethnically Chinese, but had very different experiences living in entirely different L.A. suburbs. She was by the water and I grew up east of East L.A. in Monterey Park, where the majority of the population is of Asian descent. Cambodian donut shops were as common to me as ginseng and Chinese herbal shops (as common as Wawa to a Philadelphian).

“What was it like growing up in Monterey Park?” Gu asked me. She remembered driving in as a kid, fascinated by this alternate universe. Her mom would take them out there, and they’d eat dim sum with grouchy ladies pushing carts and would stock up at the ginseng store. In the South Bay, she tells me, there were horse ranches, so she grew up riding horses. This was ridiculous to me, a foreign upbringing. What we had in common were freeways and the mom and pop donut shops that filled the strip malls of L.A.

Gu recalled a fleeting childhood memory of how excited her entire family was when a Dunkin’ Donuts opened up in Torrance. “But before we knew it, Dunkin’ was gone…and I never knew why.” Now we know why—Ted Ngoy.

Even though I grew up with the ubiquitous pink boxes, I didn’t know the amazing back story until listening to a two-part deep dive from the Sporkful podcast, entitled, ominously, “Searching for the Donut King.” Gu actually found out through her nanny. Her husband brought home donuts from a gourmet shop in Santa Monica and her nanny politely declined. “No thank you, I only eat Cambodian donuts,” she said. Gu couldn’t understand. These were really expensive donuts! She was also surprised to hear that Santa Monica, which is not very ethnically diverse, would have Cambodian donuts. Her nanny brought some over the next day. Gu was confused because it was just a plain, glazed donut. How was it Cambodian? “It’s because Cambodian people make it,” her nanny explained. “If Cambodian people make American donuts, it’s still an American donut,” Gu countered.

So she googled “Cambodian donuts Los Angeles”, and all these articles about Ted popped up, including that he had moved back to Cambodia. “How am I going to find Ted, if he lives in Cambodia, in this big, big world that we live in?” Gu wondered.

She decided to make a cold call. “Well, if what the articles say are true, and Ted is the connective tissue of all these different donut shops, I must be able to call any donut shop basically, and somebody must know him, or at least somebody who knows somebody who knows him. So I called the first donut shop I could think of, in Santa Monica, called DK’s Donuts.” She was in luck. The voice who picked up was Mayly Tao. Ted was her great uncle.

“The glazed donut that changed my life,” Gu tells me, “to the cold call that changed my life.”

The story is so dizzyingly remarkable and inspiring, it’s no surprise that it resonates with so many people. It compelled Gu, a professional cinematographer, to film and direct her first feature-length documentary.

“What was that like?” I asked.

“It’s one of these moments in life, where you leap before you look, because if you look, it’s so hard, and it’s so daunting,” Gu says. “I just had to do it. I was possessed. I just had to do it.” She asked her longtime producer José Nunez to take the leap with her. The two work together on commercials, which tend to be a lot more lucrative.

She called with her best pitch: “Not only is there no money, there’s negative money.” Would he join her and make a long-form documentary—which they hadn’t done before—and learn along the way? José was familiar with Ted’s story, having first heard it on the radio—he had to pull over to finish the story, it was so riveting.

With her producer on board, Gu applied for a camera grant. Her friend, An Tran, who oversaw ARRI’s Emerging Filmmaker Grant program (which has funded projects such as Beasts of the Southern Wild, Fruitvale Station, and Imperial Dreams), had a similar reaction. “It’s yours,” she told Gu. “I’m the daughter of refugees, my parents ended up in Arkansas in a camp…I totally connect with this story, so you got the grant.”

The stars kept aligning. All they could afford was 72 hours on the ground, but it was enough to make the teaser, which helped them get the support they needed.

What makes Gu’s storytelling so effective is how she weaves deeply personal, often traumatic, first-person interviews with Ted, his family, and first generation donut shop owners and their children, with archival footage of the Cambodian Civil War, presidential speeches and news headlines, and refugee camps in the States and overseas. We see the donut shop owners at their shops—the unglamorous hours and labor as well as the adorable moments with dedicated customers (who Gu also interviews).

Ultimately, the film shows how everything for Ted came crashing down. The partying led to Las Vegas, where Ted got sucked into higher and higher stakes gambling. He quietly returned, hiding from and lying to his family. He started borrowing money from the very people he once helped. And, when he couldn’t pay it back, signed over his ownership stake to the donut shops. He forged Christy’s name. She always forgave him. Broke, Ted and Christy moved back to Cambodia, where he cheated on her. That was the final straw. Christy divorced him and returned to the States. We see Ted admitting the severity of his betrayal, Christy’s eyes tear up, and their adult children retelling how they encouraged Christy to leave.

At nearly 80, Ted is very affable and charismatic. However, he doesn’t sugarcoat how much he has hurt Christy, his family, and his community.

We follow Ted as he visits his ghosts. He takes us quietly through the ominous rusty tanks, prison cots, and remnants of the Cambodian Civil War that killed a quarter of the population. We see Ted return to California, where he revisits his million dollar mansion and get a hollow glimpse into his ritzy former life, with a huge pool and elevator. It is beautiful and empty, and he is all alone. We meet his old Winchell’s mentor, who, at 91, still makes donuts behind the counter! Ted embraces him deeply before biting into a fresh donut, looking as young and happy as ever.

Ted visits some of the owners he once trained, and their kids. The original Cambodian donut shop owners were starting to retire, having fulfilled their dream of supporting their families and sending their kids to college. Would they be able to compete? Did they even want to? Some from the younger generation, like Mayly Tao, are taking over the family business and making their mark with original new flavors and social media savvy.

Dunkin’ made another attempt at the West in 2014, coming in with their full corporate force. They were aggressive, opening up an onslaught of locations at once, with perks and splashy marketing, and located across the street from one of the Cambodian donut shops, Rose Donuts and Café in San Clemente. Amanda Tang, whose family owns Rose Donuts, described the nervous anticipation of opening day, and the overwhelming support from their loyal customers, who lined up around the store. That Dunkin’ opening day remains the busiest day in Rose Donuts history, Amanda recalls tearfully. The Cambodian donut shop story continues; Ted only started it.

“Has everyone forgiven him? I ask.

Gu says that Ted has an almost mythical status in the Cambodian community—the legend lives on, but the details start to fade. Some didn’t know whether he was alive or dead, or where he was. “He has a very mixed reputation, he’s like, infamous,” she says. “He’s like a Yeti.”

The Donut King came out in theaters and on virtual cinema October 30th. When I spoke with Gu a few days after the election—a painfully divisive time in our nation’s history—we had yet to have our first vice president-elect who is a daughter of immigrants.

I asked her who she made the film for, and if that had changed given current events. “Everyone,” Gu says, though this was also personal for her.

“I’m not the daughter of parents who own a donut shop, but I am the daughter of immigrants who came here. I think immigrants are great and immigrants are what makes America great, and the diversity is one of the strengths of America. But while we were filming three years ago, we were hearing everything but that. Muslim ban, shithole countries…a lot of anti-immigrant rhetoric. I wanted to counter that. But more importantly, I really believe healing includes storytelling and human connection, and love and hope and optimism, and I felt this story had all of that. It made me believe in America again, and the American dream, and what can happen when you just give somebody a chance.”

The Donut King is exactly the film we need right now, to make us beam at America’s history of welcoming immigrants and refugees. The documentary closes with an inspiring speech by Republican President Gerald Ford as he implores Americans to welcome Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees.

“The United States has had a long tradition of opening its doors to immigrants from all countries. We’re a country built by immigrants from all areas of the world,” Ford says in the tape, which Gu plays as a soundtrack to images of our favorite Cambodian donut shop owners along with uplifting instrumentals that made my heart swell. Ford goes on: “In one way or another, all of us are immigrants. And the strength of America over the years has been our diversity. And the people we’re welcoming today are individuals who can contribute significantly to our society…and I believe they will make a contribution now, and in the future, to a better America.”

Then-California governor, Jerry Brown, a Democrat, famously objected to Ford’s refugee aid plan, arguing that America needed to take care of its own. “We have a million people out of work, when we have our own people taxed to the hills,” a dark-haired Brown says in an interview. “I’m just very slow to just open the floodgates and say come on in, unless we provide a way to put Americans to work.” I was shocked, incensed, hurt, and ashamed for California, watching that moment.

Ford was disappointed but pushed for the moral obligation to help refugees “escape the probability of death.” The marines had 24 hours to set up Camp Pendleton Southern California, a refugee ‘tent city’ that would eventually take in, house, feed, and clothe over 50,000 refugees from Southeast Asia. I teared up watching a rapid photo montage of marines setting up the camp that would house thousands of new immigrants, and video footage of the first refugees coming off a plane.

A film critic from Orange County shared appreciation that Gu didn’t paint the conservative area as racist and anti-immigrant. People from Little Rock and Cincinnati have written about how it made them feel great about America. “I just presented information on a time in history when we had real true leadership in a president, who showed tremendous leadership and bravery to do the right thing….I’m just trying to find good examples of the best of America.”

The film comes to a satisfying end. The credits are a sexy tumbling of colorful, inventive donuts and a catchy donut song by American rapper Yogi Barz featuring Turkish rapper MRF.

There are many gorgeous, triumphant shots of donuts upclose, the making of donuts, and donut boxes. This film will leave you with the insatiable urge to bite into a soft, fresh donut. You will feel compelled to support an immigrant-owned business. This writer ate nearly a dozen donuts (plain glazed, salted caramel glazed, blueberry cake, cronut, and cannoli filling…as well as some pound cake and scones with clotted cream and jam) as research for this article.

Prepare in advance and visit Fresh Donuts, Philadelphia’s own Cambodian donut shop! Siblings Donald and Van Eap have owned and operated the community mainstay in West Philadelphia’s Mantua neighborhood since 1991.

Diana Lu is a city planner who likes to write. She has spent more than ten years in the nonprofit, public, and media sectors working on economic development, placemaking, and resource redistribution. Diana leads the Germantown Info Hub, a community-centered journalism project that shares information for and by Germantown residents, and community engagement editor for Root Quarterly, a Philadelphia-based print journal. She previously served as the Community Engagement Editor for PlanPhilly, WHYY’s planning, design, and development news project. Diana serves on the ‘Change the Narrative’ committee for the Women’s Economic Security Initiative, board of the Independence Business Alliance, and finance committee for Women’s Community Revitalization Project. Her work in economic development and community engagement in the AAPI community was honored by Governor Tom Wolf’s Commission on Asian Pacific American Affairs in 2018. Diana has lived and relied on public transit in Los Angeles, Chicago, Brooklyn, San Francisco, and Paris, but became a proud SEPTA rider in 2009. She holds a Masters in City Planning from the University of Pennsylvania Stuart Weitzman School of Design and a B.A. in Urban Studies and French from Vassar College.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.