23 Jul Starting Fires with Dedza

BY BEDATRI D. CHOUDHURY

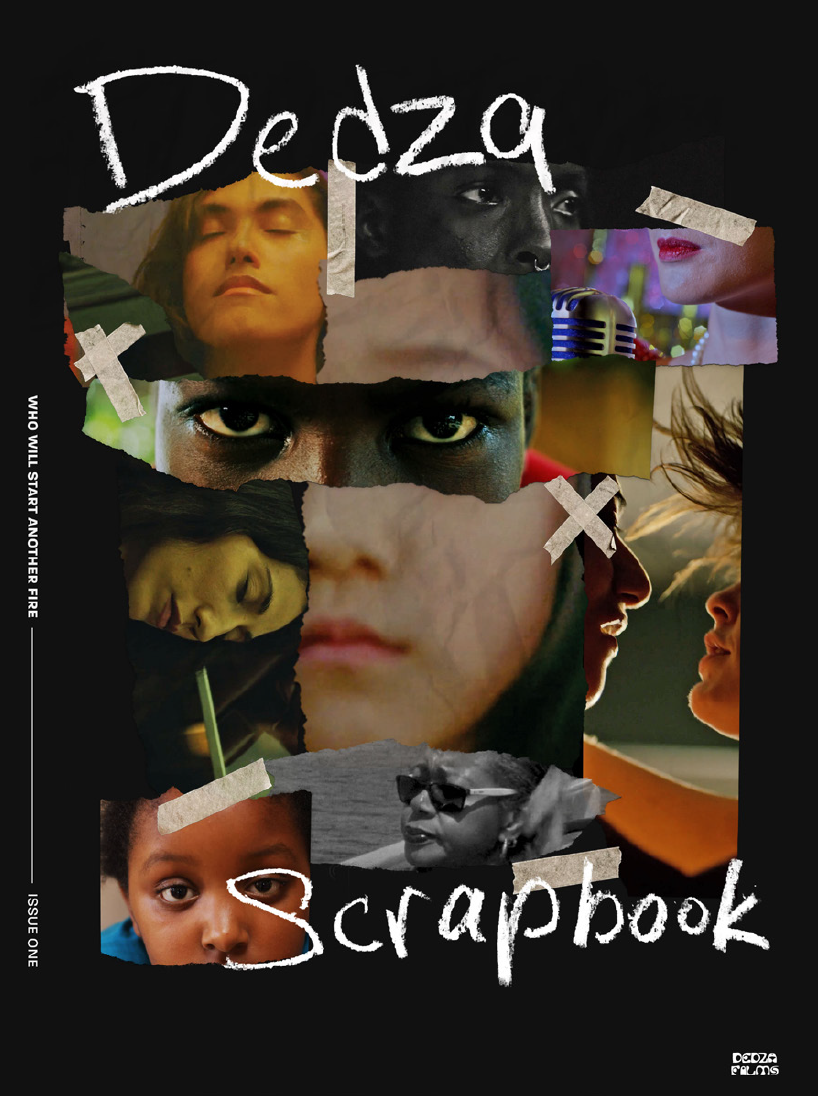

Who Will Start Another Fire is a collection of nine films by emerging filmmakers from underrepresented communities around the world, presented by the new distribution initiative Dedza Films.

cinéSPEAK is honored to be a presenting partner of this incredible short film program. Your ticket purchase directly benefits the filmmakers, this important project, and our cinema. Buy Tickets Here.

Dedza is the city in Malawi where Kate Gondwe made her first short film; the city her family calls home; and the city of the poet Jack Mapanje. When Gondwe founded a distribution platform, she decided to name it after the city. Dedza Films aims to work with “the next wave of emerging filmmakers and underrepresented communities.” “Our mission,” their website reads, “is to curate, community build, and partner with other initiatives and organizations that are focused on changing the landscape.”

“Access to seeing ourselves on a screen is why I am building Dedza,” the organization’s founder and president, Kate Gondwe, tells me. “Unfortunately, the systemic racism in this industry has prevented stories by Black and Brown filmmakers from being projected on the screen since the beginning of its formation.” Therefore, Dedza took the name for its first anthology of short films from a Mapanje poem. “Who will start another fire?” the poet asks in “Before Chilembwe Tree” (1981). Dedza removed the question mark in their bid to answer his call.

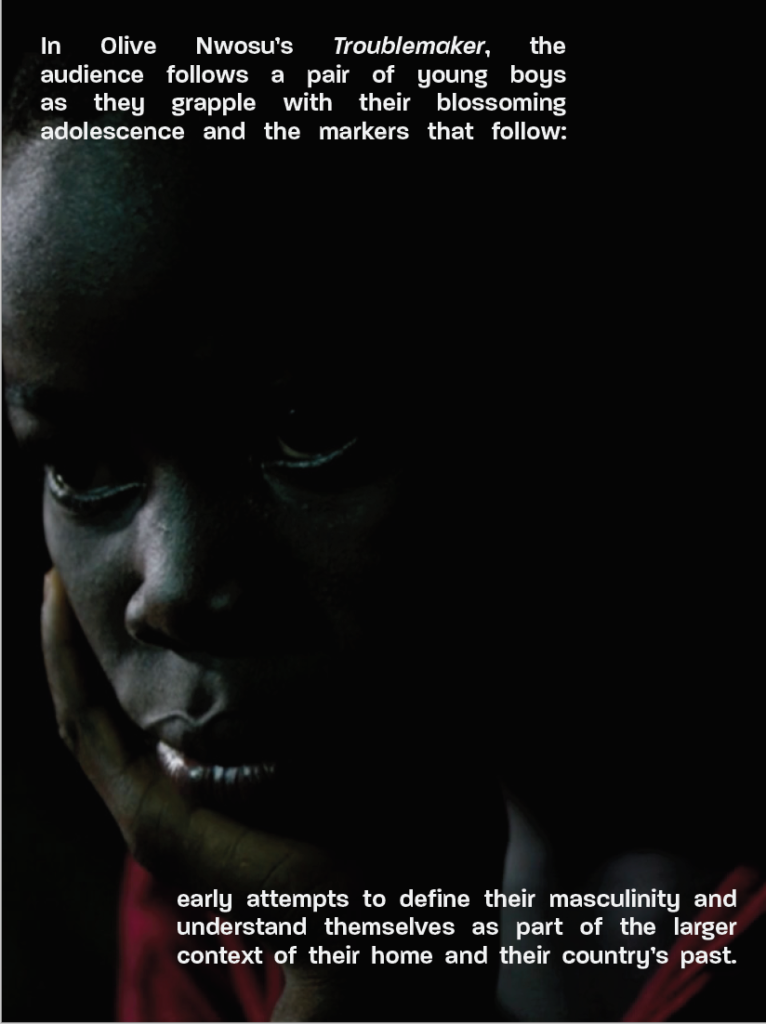

Who Will Start Another Fire features films by Alex Westfall, Peier Tracy Shen, Nicole Otero, Jermaine Manigault, Nicole Amani Magabo Kiggundu, Olive Nwosu, Samira Saraya, Faye Ruiz, Lesley Steele, and Emily Packer. “I’ll never forget our first screening. Seeing a community of all people coming in and seeing Who Will Start Another Fire ignited a fire in me,” Gondwe says. Beyond the treasure trove of the films, the program is accompanied by the Scrapbook that features writings on each film from BIPOC emerging film critics. It’s not enough to just start a fire; there have to be storytellers to record and discuss these fires so that they spread beyond the lines our societies draw.

Aaron E. Hunt, Dedza’s Vice President and Editor-in-Chief, was one of the first few people Gondwe contacted after she pitched the idea of Dedza Films to Kino Lorber, where she was interning in 2020. Hunt, who is a culture journalist with bylines in Mubi Notebook, Filmmaker, and American Cinematographer, was brought on board because “I was more focused and have always been more interested in distribution, but wanted to see how Dedza could support critics of color,” Gondwe says. With the Scrapbook, Hunt rose to the occasion.

“I think it started during the pandemic, after the murder of George Floyd. Kate and I were frustrated at the way that various film organizations, companies, corporations were responding with vague, open-ended statements,” Hunt says when I asked him about Dedza and what inspires his work here. “They were all donating when, historically, they had not really done anything to alleviate structural racism. The idea is to build long-standing efforts at growing something that counters this racism.” Short films typically garner far less attention than feature films. While Who Will Start Another Fire centers on short films and ensures a place for them, the Scrapbook pushes the films to occupy spaces that lie beyond the act of seeing and watching. It calls for a deeper engagement with the films in the program and constructs an ecosystem around them where they’re not just objects of visual pleasure, but also cultural products that get dissected and analyzed.

All the critics who have written for Scrapbook are, in Hunt’s words, “actually emerging critics of color. We see a lot of these programs and initiatives for apparently emerging critics, but you have already read their published works somewhere. The whole point for me was to bring on people like I was unfamiliar with, and elevate their voices.” He found each of the critics—Alexandra Bentzien, Abiba Coulibaly, Sarah John, Yaira Matos, Ana Velasquez, Horea Abdourahman, Devon Narine-Singh, Robyn Matuto, Martez Warren, and Michael Piantini—from a tweet “that got retweeted a lot of times.” They had to submit one writing sample but it didn’t have to be a film review. “All I was looking for was an understanding of intersectionality. The knowledge that a film doesn’t have to be a race film or a gender film or an identity film. That it could be all of those,” Hunt explains when I ask him if there was a criteria for selection of the writers. He was, he confesses, a “little partial” to people whose life experiences mirrored the narratives of the films.

While some of the essays are personal and some more objective analyses, the laudable constant in the Scrapbook is the design aesthetics and layout of the publication. Xan Black, Dedza’s Head of Design, has a background in designing key art for films along with posters. There is no way of knowing from the Scrapbook, but they tell me that they have never designed something like this before. “That feeling of not really knowing what the standards were with making the Scrapbook helped. I had a lot of freedom to decide on an aesthetic: the films themselves are very colorful, and I wanted to highlight that. The cover was the first thing I designed,” Black says. For them, a nonbinary creative person of color, the intersections between film and writing, and of the writers’ personalities, had to be highlighted. There is an openness and abundance to the way Black lays out the words and images in Scrapbook–a refreshing relief given how film criticism is continually being pushed into cramped corners within mainstream journalism.

Hunt’s desire to hold space for these newer voices in criticism finds a physical manifestation in Black’s layouts; where most publications print reviews over 1-2 spreads, Black uses 4 spreads for each essay. In order to occupy intellectual space, it is essential to physically occupy cultural spaces that have been kept away from writers of color. Black’s Scrapbook pages—with their page-wide images, playful fonts, bold blacks and reds, and the masterful use of negative space—make a claim for widening space for the writers’ words. “It’s like expanding the run time for these shorts. We want people to spend more time reading these essays, think more about what the writers have to say,” Black says when asked to explain their guiding philosophy behind the design.

Film criticism, especially when written by emerging critics of color, doesn’t enjoy a proximity to the formal film distribution industrial complex. “When people start out, the first places to accept their writing are niche, often obscure websites and blogs,” Hunt says, “The whole idea of the Scrapbook was to allow film criticism a space that is right alongside distribution channels.” Within an ecosystem that we are taught to treat like a finite pie, an organization like Dedza, with its programs and Scrapbooks, dares to do something that is quite the opposite—to hold space, to expand it, so others can come and stand side by side. Within this new space, there is enough room; for people to make films, for people to watch them, for people to write, and for people to read. To light fires and then pass on the spark. To know that there will always be someone to start the next fire.

Who Will Start Another Fire is available to watch online here.

Since October 2013, cinéSPEAK has functioned as a mobile cinema—producing independent film screenings in-community across our great city. For most of our existence, cinéSPEAK has been run by passionate volunteers. Over the last 7 years, we’ve produced nearly 70 film screening events in-partnership with dozens of Philadelphia’s most reputable arts, cultural and grassroots organizations. Read more here.

Bedatri D. Choudhury works with documentary films and is a culture journalist. She is a member of cinéSPEAK‘s 2021 Editorial Collective. Born and raised in India, she lives in New York City.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.