02 Dec How the Film Work of Punk Legend Brontez Purnell Evokes and Transcends the Legendary Marlon Riggs

BY ALEX SMITH

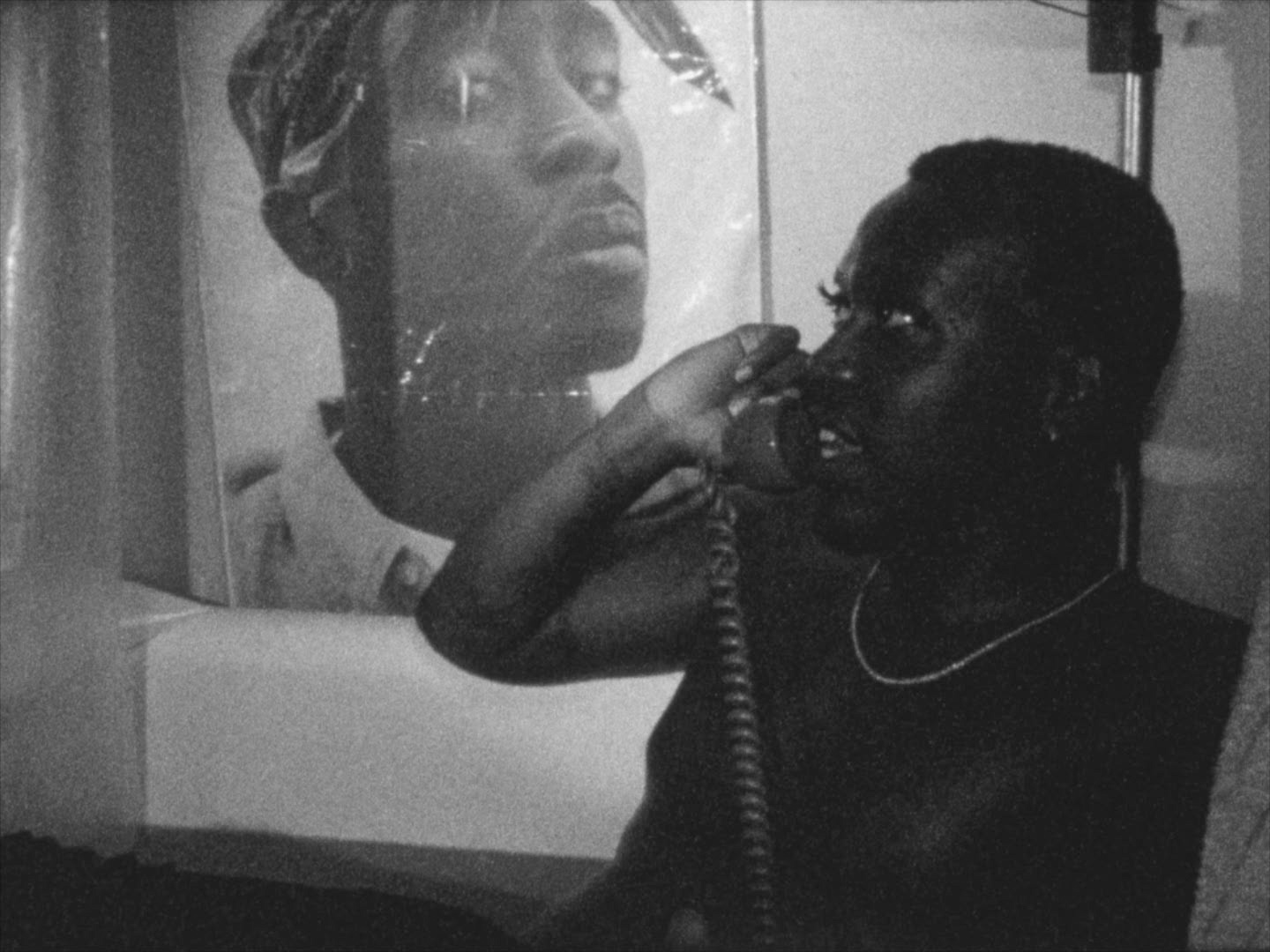

“What’d I do today? Oh my god, I got some new jeans.” This triumphant opening line is the start to Brontez Purnell’s 100 Boyfriends Mixtape, the first moment we see the film’s lone subject: a gay Black man named DeShawn, played by Purnell himself, navigating an estrangement from his own personal life in San Francisco’s gay community. He’s sitting in a tub while wearing those jeans, soak-fitting them–it’s a hilarious meet-cute between audience and artist, between us, the viewer, and the charming, if not somewhat troubled, DeShawn. The camera rarely moves, subtly ebbing (not so much flowing) while DeShawn proselytizes into the phone, his friend on the other end of it no doubt enraptured as DeShawn unspools his day into a landline.

“Men suck and I’m sick of fucking them,” DeShawn reminds us, as he submerges himself underwater, the camera pulling back and letting him ruminate on any number of things both humorous and melancholy. This dynamic, the push and emotional pull of Purnell’s short film is a blast of tonal shifts in a perfect play on genre. There are moments of contemplation spread out over the film’s eight minutes and a meditation on the turmoil of being Black, queer, and HIV+ in a community that de-centers Black excellence and rewards white mediocrity. DeShawn isn’t all sass despite his overt nature, despite the face and voice he cobbles together in the presence of his unseen friend.

“Multiplicity is all through that text,” Purnell relates via Zoom. When asked what inspired the happy-sad-as-normal duality, practically within the same frame of a scene, Purnell assures us that, “It’s storytelling, it’s life.” He continues: “It’s a funny question to me, people often ask me, ‘Why do you have such sad shit next to such funny shit?’ I’ve studied theater all my life, it’s a pretty basic trope. Like, Shakespeare did it. If you go back and study Shakespeare, through all this heavy shit there’s poop jokes, fart jokes, all types of stuff. The idea is, to get to pathos you’re supposed to run a gamut of feelings. Writing is two dimensional, kind of a limiting form–it’s really hard to get at how the human mind works because writing must always be presented in a litany. When in actuality, let’s say you’re walking through a Kroger parking lot and someone hits you with a water balloon–all at once you’re like, ‘Oh what’s that? Oh that’s exciting! Oh that’s wet and I’m mad and need to go beat this person’s ass! Oh this is funny and ridiculous!’ These thoughts are running simultaneously, but once presented in a litany it appears kind of ridiculous, but that is how the human mind works. In writing, people defintely pick these types of voices where it’s like, I’m either writing a total disaster narrative, a feminist of Black tragedy, and I must keep on that track to make sure it tracks for people…but there’s no way to get at how complex and 3-D the human mind is.”

The juxtaposition of DeShawn’s humor and pathos in 100 Boyfriends Mixtape is jarring, but believable. It’s hard not to find the humor in seeing him soak-fitting his jeans, backdropped by a shower curtain adorned with rapper Tupac’s face, while dropping serious tea about former drug-dealing, now bougie and adopting gay couples he’s had trysts with–while still being so engrossed in the narrative when DeShawn discloses his HIV status or rails against what he perceives as the materialism of queer life in the Castro or confronts masculinity in general. To that end, it could be stated that Tupac, the only other human visage that appears, is a co-star–at least conceptually, as he represents here both an ironic and aspirational relationship with Black masculinity. According to Purnell, Black masculinity remains nebulous. “I don’t define [Black masculinity]. It’s so many different things to so many different people. At the risk of using an overused statement, Blackness is not a monolith, masculinity is not a monolith–more than that, it is infinite multiverses. The problem is when cultural stereotypes or archetypes are set, they never really go away. So I think the work we do now is trying to either flip those precepts or run parallel with them, as a way to have more options.”

In that light, 100 Boyfriends Mixtape is available as part of a small collection of shorts on the Criterion app dedicated to and inspired by the work of Marlon Riggs, a Black queer filmmaker whose late 80s and early 90s works include such stand-outs as Tongues Untied and Ethnic Notions. Riggs was known to intersperse narrative and fictionalized accounts with documentary, dance, and poetry, often within the same film. The results are beautiful, powerfully stated pieces of fragility stretched over a filmography that truly inspired a wide berth of Black and gay filmmakers. While there are moments in each of the films in the collection that recall Riggs’ work–the elegiac poetry of Shikeith’s A Drop Under the Sun or the revealing look at modern ball culture in Elegance Bratton’s Walk for Me, and of course the subtle humor and single-camera perspective in 100 Boyfriends Mixtape–each film is its own entity, distanced from Riggs’ oeuvre by time, tools, and the other influences.

“I feel like the second I got to San Francisco, I did not not see Marlon Riggs’ work somewhere,” Purnell says. “It was always there. Like, whoever defined us as the new guard of Black Bay Area filmmakers, they were gonna be like, ‘Do you know Marlon Riggs’ work? Do you know Marlon Riggs’ work?? Brontez, have you ever heard of Marlon Riggs??’ And I’m just like, ‘Yes!’” For Purnell, there’s a personal connection; Riggs’ Long Train Running, a documentary on a blues club, features Purnell’s uncle, the family member who taught Purnell how to play guitar. Weirdly enough, the uncle doesn’t speak in the actual film, yet Purnell still keeps the documentary and Riggs’ work close to his heart.

“Watching Tongues Untied too, it was his story in the 80s–‘I was in the Castro and I didn’t fit in’–and of course it echoes of all of our experiences, and I don’t know, to let the white girls tell it, they don’t feel like they fit in the Castro either! It’s all kind of like an artifice and a facade. His era was probably more defined by that, but I’ve always been kind of an Oakland girl.”

As the film moves through DeShawn’s complex emotions, Purnell’s directing, comedic timing, and naturalistic (yet somehow still dramatic) acting turns 100 Boyfriends Mixtape from what could have been a dour spoken word piece dripping with cynicism into a remarkable character study. In the shadow of Riggs’ legacy, there is hope and a budding filmography wrought with complex story-telling, genre bending, and tonal shifting elucidations. It’s within this pantheon that Brontez Purnell and his art will certainly fit.

100 Boyfriends Mixtape is now streaming on the Criterion Channel as part of the ‘Inspired by Marlon Riggs’ collection.

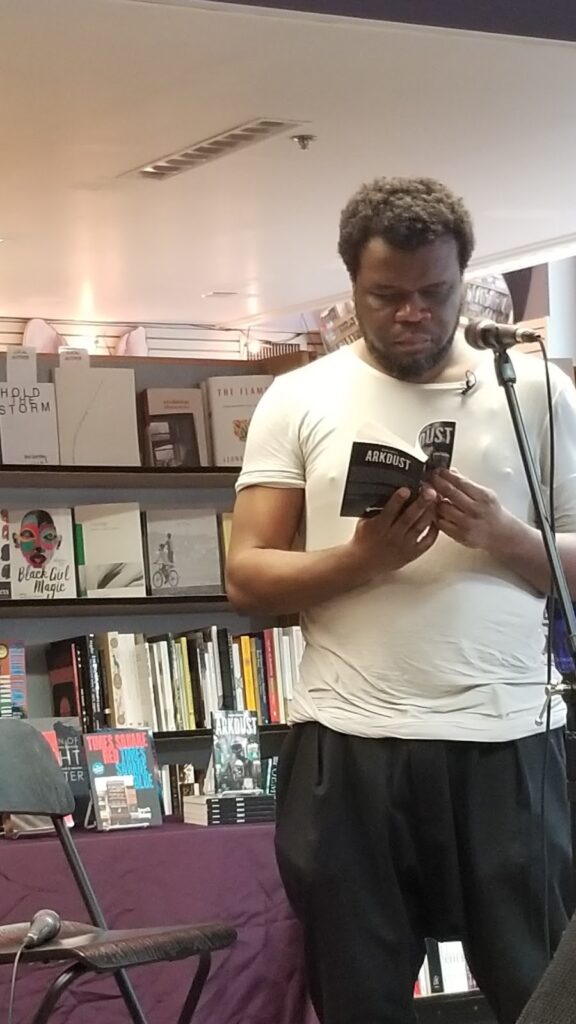

Alex Smith is a sci-fi writer (The Resistance web-series; Black Vans comic book), artist, musician (art-punk bands Solarized, Rainbow Crimes), activist (Metropolarity queer sci-fi collective) and cultural/arts critic (Pitchfork, The Key, Bandcamp, Philly Gay News). He is a recipient of the Pew Fellowship in the Arts and soon to be published author of the sci-fi/cyberpunk/super-hero/Afrofuturist short story collection ARKDUST, forthcoming from Rosarium Publishing

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.