20 Jul Celluloid Fires and Coalitions: The History of Philadelphia’s Film Labor

BY C.M. CROCKFORD

Even the most jawn-centric, born and raised Philadelphia resident, if asked, might dismissively condense the city’s filmmaking history into a few famous titles. Philadelphia, of course, then there’s the Rocky series, M. Night Shyamalan…oh, and Blow Out, right? The Fourth of July scene? Studios don’t often call on Philadelphia for location shoots, and the city may never be seen as a truly director-friendly town. But whether its residents know it or not, filmmakers, photographers, and film and television workers have always been a part of Philadelphia’s labor force and cultural history: from Lubin Studios and “the first American studio mogul” to The Sixth Sense.

Still, even if Philadelphia has historically been a hub for filmmaking, the city is often a challenging place for film crew workers. The work isn’t as consistent as it is in some other cities, especially compared to the West Coast, where it’s cheaper and easier to shoot. The unions are led by non-Philadelphians, who may have different priorities than the workers here. Plenty of producers also have a bad impression of the local union workers and prefer to shoot elsewhere. But many of the problems with film production in the City of Brotherly Love–and in East Coast filmmaking as a whole–were there a hundred years ago as well. Ultimately Philadelphia’s film labor efforts involve a tantalizing series of knowledge gaps, what-ifs, frustrations, and plans that never came to fruition.

The Early Years

Philadelphia isn’t always seen as a movie-friendly city, but it was an early hub for filmmaking and photography. According to Andrew Ferrett, director of the 2017 documentary Before Hollywood: Philadelphia and the Invention of Movies, the moving picture was a staple of life here decades before the dawn of the camera. Charles Willson Peale circa 1787 operated a regular show, using light and paint to sustain the illusion, mere blocks from the National Convention Center. His son Franklin also worked on early photography, and the city was eventually filled with what Ferrett called “restless experimenters”–entrepreneurs and filmmakers trying out as well as perfecting different cameras and processes for capturing photography. Coleman Sellers, Peale’s grandson, even patented one of the earliest motion picture cameras here.

The Philadelphia-based optometrist Siegmund Lubin deserves the credit for founding the Lubin Manufacturing Company in 1902. Over a thousand silent films were produced both at Betzwood Studios in Montgomery County, as well as in “Lubinville,” his studio and processing plant on what is now 20th Street and Indiana Avenue. It’s all too easy, however, for history to forget the workers who quite literally made these movies: the hair and makeup people, the special effects artists and production designers, and the processing plant employees who earned Lubin a reputation for pristine film prints. The company’s logo accordingly displayed the Liberty Bell and the slogan “Clear as a bell.”

Montgomery County Community College History Professor Emeritus Joseph Eckhardt calls Lubin “America’s first movie mogul.” However, Professor Eckhardt explained to me that compared to his successors, Lubin was unusually “paternalistic” and generous with his workers. “Many young girls in the cutting and assembly rooms were making more than their fathers who were working 60 hour weeks in factories,” he wrote. All of them received hot lunches, free food if they worked late, and Lubin often paid for medical bills and, most shockingly, death benefits. As Eckhardt points out, “In return, of course, Lubin expected devotion and loyalty from his [work] ‘family.’” This may explain, however, why Lubin’s workers never took any action against him. They were simply treated well.

Yet despite his wealth, marketing savvy, and success as a boss, by 1912 the mogul made some egregious errors. He stuck to one-reel features when the public increasingly demanded longer films, and he likely expanded too quickly, launching multiple studios in Betzwood, Los Angeles, and Florida.

There was also the infamous 1914 Lubin vault fire when, despite the plant’s thorough and commendable safety measures, celluloid gas ignited inside the plant, resulting in several massive explosions and rapidly spreading fire across Indiana Street. One boy likely died as a result of severe burns, though Lubin actor Harry Myers–best known later as the drunk millionaire in Chaplin’s City Lights–had tried to save his life, smothering the flames surrounding him. Only 20 minor injuries were sustained otherwise, in part because of the vault’s integrity and safety measures. This was also because of the genuine heroism of plant personnel, who were already fighting the fires back when the city’s emergency services arrived, and the studio’s actors like Myers and Charles S. Schultz. Local boxer and actor Willie Houck, evidently just visiting that day, even aided several young employees, about to jump, in evacuating the roof.

Yet the Lubin Manufacturing Company might have been doomed regardless of the fire. The outbreak of World War I destroyed Lubin’s income selling films to foreign markets, and he faced legal trouble thanks to his “vertical” distribution scheme: making, selling, and showing his films in theaters he owned. The vault’s destruction merely hastened his company’s decline. By 1916, Lubin declared bankruptcy and soon returned to his former working life as an optometrist. Jake Blumgart writes in the Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, “after the company’s early collapse, the city never again attained a prominent role in the nation’s filmmaking.”

Early American film pioneers and productions often revolved around West Orange, New Jersey and New York City. But the reality is the same in both 1923 and 2023: ultimately, shooting movies on the West Coast is easier than staying on the East. Studio land in New York and Philadelphia costs more, the weather isn’t as consistent, and in the early 20th century, there were far more workers on the other side of the country. Thomas Edison’s monopolizing Motion Picture Patent Company was likely the final straw then for the first studios and independents. By the late 1920’s, they were all heading for the West Coast, especially (of course) Southern California.

Philly Film Labor Unionizes

Since the rise of Hollywood, Lubin’s bankruptcy, and the 1924 closure of Philly’s final studio, The Betzwood Film Company, Philadelphia film crew workers, technicians, and filmmakers have had three basic options. They can either (a) move to California, (b) work freelance in non-union roles on local independent productions, or (c) join International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE) Local 52 so they can work on the occasional big studio movie like Shazam or Creed. But the keyword there is “occasional.” The Greater Philadelphia Film Office (GPFO) actively works to promote film productions in the city. But often when they want the movie to look “gritty” or blue-collar, studios opt for saving money and shooting in Pittsburgh. In fact, the GPFO was the only film commission without any government funding during the early COVID pandemic.

Despite its byzantine structure, the organization of Philadelphia’s film unions haven’t actually changed in about three decades. In 1995, the city’s film crew workers chose to leave IATSE Local 487, which was based in Baltimore and Washington DC, and join the IATSE New York branch, Local 52. Their jurisdiction includes Connecticut, Delaware, and most of Pennsylvania. However, Pittsburgh’s film crew has their own branch, IATSE Local 489. With the NYC Teamsters Local 817 separately running the set’s truck drivers, New York leadership is firmly in charge of the film unions in Philadelphia.

GPFO head Sharon Pinkenson told Philly Mag in 2016 that IATSE Local 52 is part of the city’s mixed reception in Hollywood. “They have a reputation for being very difficult, and I cannot tell you how many producers have come to me and said that they wouldn’t work here because [of them].” However, this comment came after local film technicians criticized the Film Office for not bringing more work into the city (especially as compared to the Pittsburgh Film Office). In a more recent comment via email, Pinkenson told me, “Our office supports and advocates for both union and non-union film workers; always have, and always will.”

An Inquirer quote from David Haddad, former President of the Pennsylvania Film Industry Association, might explain this city’s movie problem more succinctly: “The only reason no one’s filming in Philadelphia is there hasn’t been a script that works.”

For all its idiosyncrasies, striking visual locations, and strong folk culture, Philadelphia hasn’t been a primary filmmaking location in a long time. But what stood out to me in my research wasn’t just the heroism of the Lubin employees, or the typically blunt statements of Local 52 reps. It was also the vigilance of the unions and union members across the years, even in an industry subject to all kinds of exploitation.

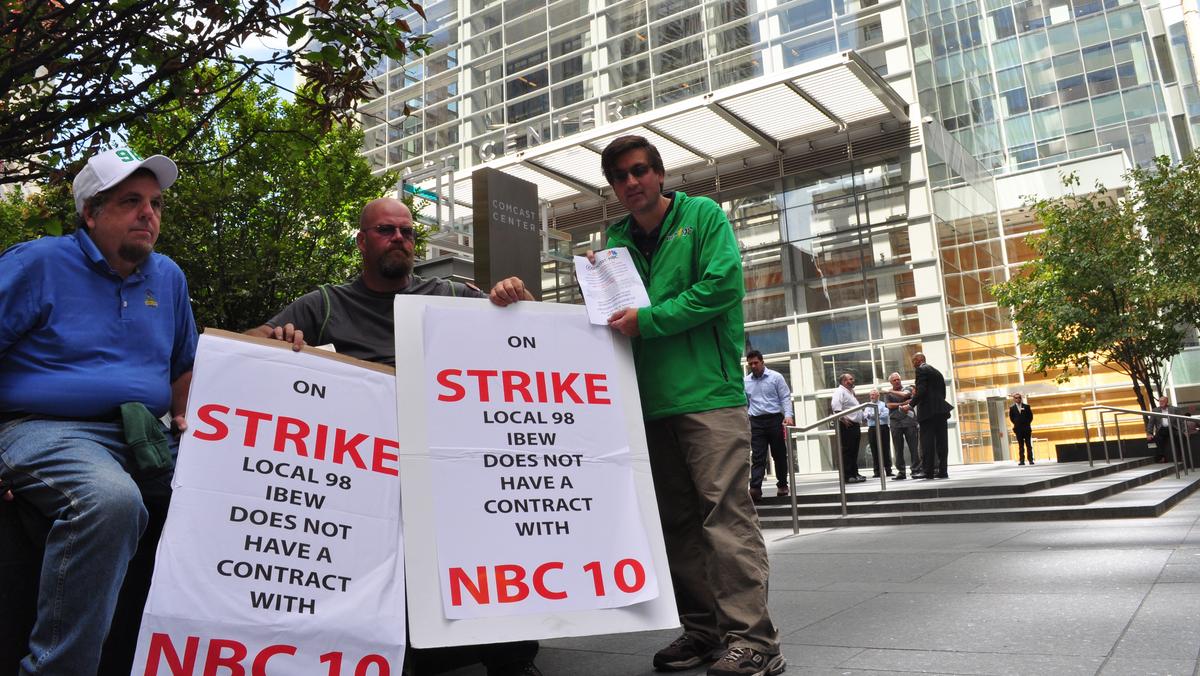

In 1973, IATSE struck against station KYW-TV in multiple cities, including Philadelphia–this resulted, ironically, in KYW sending non-union crew to cover the AFL convention that year. In 2015, IBEW Local 98, made up of electricians, camera workers, and technicians, settled a three week strike. When the Greater Philadelphia Area production of Apple TV+ series Sinking Spring was shut down earlier this May, credit was given to not just the striking local Writers Guild of America (WGA) members, but also members of IATSE and Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) Philadelphia Local, picketing right alongside them. IATSE and SAG members repeatedly picketed alongside striking WGA members in the city, and now SAG are officially on strike themselves.

More than 100 years after Lubin Studios closed, there are still union and non-union filmmakers, screenwriters, craftsmen and technicians who make their living shooting films and television news, cable productions, and shorts around the Greater Philadelphia Area. And in recent years, the number of projects filming here has picked up and many technicians have been able to find more regular work. TV series and movies such as Creed 2, Dispatches From Elsewhere, Mare of Easttown, and Servant all brought work to the area–hopefully this trend will continue. Philadelphia’s film and television workers may not always get the recognition they deserve. But they should still be regarded as part of the same local tradition of class solidarity, struggle, and the art of making movies.

*Featured Image: Image of NBC10 Technician Ken Agatone, right, picketing outside the Comcast Center with two other IBEW Local 98 union members in 2015. Image Credit: Alison Burdo.

Edits as of August 22, 2023: Shazam was mentioned in the article as a film that was shot in Philly but only a small portion was shot in the city. Additional information was added about how Philadelphia workers joined IATSE Local 52. The Teamsters were originally covered by Local 107 but are now covered by Local 817. More context was added about the quote from the Greater Philadelphia Film Office. More film and television productions that have been located in the city in recent years were added to the article.

C.M. Crockford is a neurodivergent writer and editor originally from New England. His work has been featured in the Cleveland Review of Books, In The Mood Magazine, Vastarien, Vast Chasm Magazine, and Broad Street Review.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.