26 Oct Rich People Make the Best Movie Monsters

BY JOE GEORGE

I was an unusually fearful child. It only took the trailer for Friday the 13th Part VI to keep me awake and staring through the window all night for signs of Jason Vorhees. A glance at the VHS cover for Ghoulies was enough to convince me that my toilet was infested with little green men.

I still have plenty of sleepless nights as an adult, but not because I watch too many horror movies. Freddy Krueger doesn’t keep me up at night, but my unstable job prospects do. When my phone rings, I don’t expect a creepy voice telling me that I’m going to die in seven days, but I do expect a bill collector threatening to slaughter my credit score.

These two experiences have more in common than one might think. Misers and plutocrats have been mainstays on movie screens since the silent era and have been the villains in films of every category. But no genre has revealed the evil of the 1% more consistently than horror. Portrayals of the horrid rich may have changed over the years, from secondary figures whose actions release evil on the world to the actual monsters themselves, but the point is always clear: the love of money is the root of all kinds of evil. These films not only terrify audiences better than those about imaginary creatures, but they also keep us focused on real world threats. By helping us visualize the fears that affect our everyday lives, horror films about wealth inequality can inspire us to continue working for change.

Greed in the Golden Age of Cinema

The first horror movies of the early 20th century often featured supernatural villains, but these metaphysical terrors relied upon material reality. The gothic halls of James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931) and the torture dungeon in The Raven (1935) require wealthy landowners to subsidize the setting. King Kong only makes it to America in his 1933 debut film thanks to the financers backing exploitation filmmaker Carl Denham (Robert Armstrong).

Sometimes, the villain’s financial status drives the plot, as with the real estate deal that brings the vampire out of Transylvania in 1931’s Dracula and its 1922 unauthorized German forerunner Nosferatu, but the connection between money and monstrosity often remained unsaid in the movies of this era. We rarely saw anything as striking as the factory in Fritz Lang’s expressionist masterpiece Metropolis (1927): workers filing into a factory shaped like a twisted face with an open maw, punctuated by a title card that declares, “Moloch!”

Sci-fi influences and Cold War xenophobia dominated horror of the 50s and 60s, in which pure-hearted American scientists in government bunkers took the place of creeps in castles (as a warning in Frankenstein put it) “treading in God’s domain.” While rich villains still regularly appeared in these films, the movies often became morality tales about the failings of those who wanted to make a quick buck.

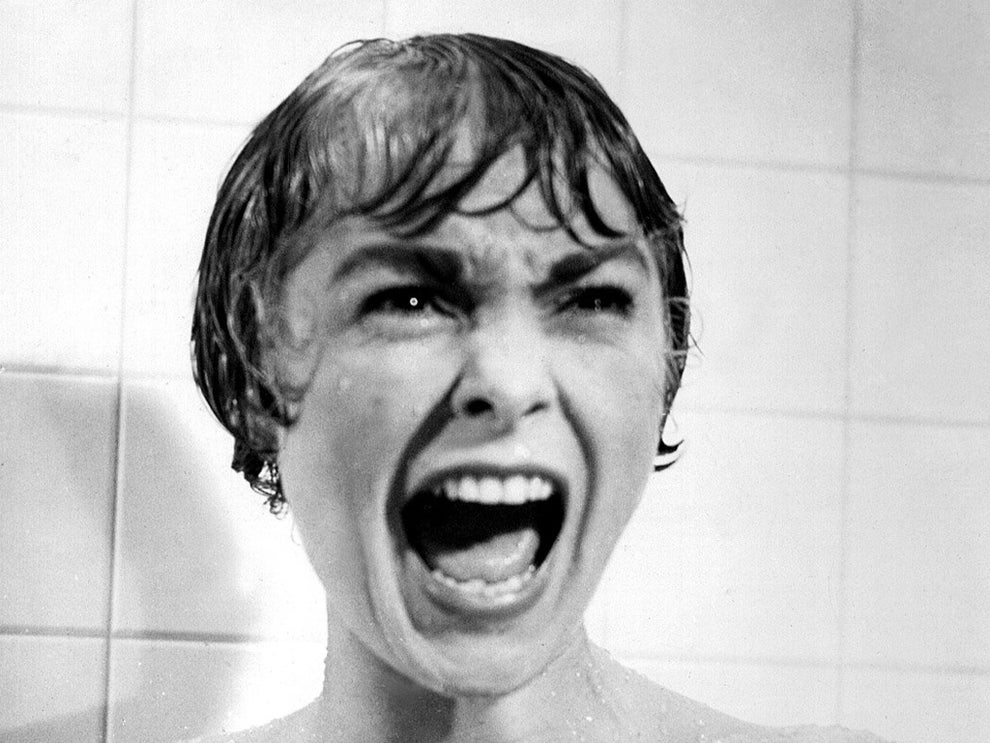

William Castle camp classics The House on Haunted Hill (1959) and 13 Ghosts (1960) may feature devious millionaires and property owners, but the films’ pleasures come from torturing the rubes coaxed into staying in the haunted houses for financial reward. Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) provides the most famous example of this change in focus. Early in the film, the boorish drunk Tom Cassidy (Frank Albertson) flaunts his cash and harasses Janet Leigh’s Marion Crane, but he escapes relatively unscathed. Instead, it’s Marion who suffers, first from the guilt she feels after swiping Cassidy’s money and then from Norman’s knife when she stops at the Bates Motel.

These early movies may have focused on the suffering of lower classes, but they always acknowledge the rich as the shadowy force behind the horror. By the 1970s, moviemakers were ready to directly portray capitalism as an evil unleashed on the world.

Cruel Capitalism and New Hollywood

Fueled by a love of classic cinema and countercultural ideals, the so-called “New Hollywood” directors of the late 60s and 70s took advantage of a system that privileged artistic expression over studio budgets to attack capitalism. A popular example of this new approach appears in Jaws, Steven Speilberg’s 1975 blockbuster about a great white shark attacking a tourist-friendly New England island over the fourth of July weekend. It’s easy to blame the island’s Mayor Vaughn (Murray Hamilton) for forcing Sheriff Brody (Roy Schieder) to keep the beaches open, but the film takes time to remind us that he’s a victim of an economic system. As he and many others remind Brody, it takes only one bad holiday weekend to leave them all destitute.

But perhaps the most enduring example occurs in Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979), which introduced one of cinema’s most accurate portrayals of capitalism in the form of the Weyland-Yutani Corporation. More than a battle between Sigourney Weaver’s Ellen Ripley and a fast-growing xenomorph with acid blood, the real conflict of Alien is between workers and the company that employs them. The film opens with a computer system operated by the company disrupting the sleep promised to the crew of the mining ship Nostromo. Weyland-Yutani has roused the crew to force them to investigate a wreck on a nearby planet. When Parker (Yaphet Kotto) and Brett (Harry Dean Stanton), engineers at the lowest end of the pay scale, rightly insist that they get more pay for the extra work they’re doing, captain and company man Dallas (Tom Skerritt) protects his employer’s bottom line. He snaps at them about their contracts, dismissing his fellow workers as insolent for wanting compensation for their labor.

Despite Dallas’s concern for the company’s well-being, Weyland-Yutani does not care about him or his co-workers. When a face-hugging alien attaches itself to crewmember Kane (John Hurt) during the investigatory mission, Ripley follows safety protocol and keeps him in quarantine. But the company responds by dispatching the android Ash (Ian Holm) to override these guidelines and to protect their interests. Ash allows Kane to enter the ship, where he can study the creature as a potential company asset.

No matter how many people die in the process, Weyland-Yutani remains focused on profits in each of the Alien sequels. The company never learns from its mistakes because it only loses parts of its replaceable workforce, not significant amounts of money. Like the corporations we deal with every day, Weyland-Yutani sacrifices as many people as it wants to, over hundreds of years, to maintain a profit.

The deep-space setting of the Alien franchise may be a million miles (and several decades) from Jaws’s Amity Island, but they both face the same threat: capitalists killing people with a remorseless abandon that most associate with aliens and sharks.

Mammon is the Monster of Modern Cinema

Despite their anti-capitalist themes, Alien and Jaws helped establish a blockbuster formula that eventually allowed studios (and the megacorporations buying them) to regain control over the creative processes. At the same time, the liberal movements of the 70s gave way to a conservative uprising in the 80s, as various groups waged “culture wars” against any form of entertainment that did not valorize free market capitalism and white middle-class American values.

But horror has never been part of the mainstream, and the genre remained committed to revealing the terror of capitalism. The great slasher franchises of the period – Halloween, A Nightmare on Elm Street, Friday the 13th, and Child’s Play – all show the rotten core in the promise of the American Dream. Each of these movies features a place or item sold as “safe” to middle-class families: the suburbs, a summer camp, or a toy doll. And in each case, the previous generation’s failures summon demons to threaten the kids.

Other filmmakers moved past subtext to make the rich into overt monsters of their movies. John Carpenter’s They Live (1988) takes an alien-invasion premise from the 1950s and turns it into an attack on Reaganomics, as homeless men Nada (Roddy Piper) and Frank (Keith David) receive magic sunglasses that reveal the truth of the power structures surrounding them. Through that lens, Nada and Frank see the upper classes as grotesque aliens and media around them as simple subliminal commands: “Buy” and “This is your God.” The 1989 Brian Yuzna film Society puts a finer and gooier point on the matter, with its story of a Beverly Hills teen who discovers that his adopted family and their friends are carnivorous creatures. The movie climaxes with a hideous scene that’s half orgy and half feeding frenzy, in which the creatures ooze together into a mass of body parts and devour members of the lower classes.

While the 2000s were filled with Asian horror remakes such as The Ring (2002) and torture porn franchises that followed Saw (2004), none of which left room for capitalist critiques (though one has to wonder how the Jigsaw Killer of Saw pays for his death traps), the financial crisis of the 2010s made wealth inequality impossible to avoid. The Purge (2013) channeled civil unrest into a raucous set of movies about privileged people murdering the lower classes under the auspices of an equalizing bacchanal. Jordan Peele’s Us (2019) offers a twisty tale of doppelgangers and nostalgia to remind viewers of the inextricable link between the poor and the middle class. And the socialist genre movies of Korean director Bong Joon Ho finally found a mainstream American audience with the Academy Award-winning thriller Parasite (2019).

How Horror Defeats the Monstrous Rich: An Analysis of Ready or Not

No movie captures current anger toward the rich better than Ready or Not, a horror-comedy romp from directors Matt Bettinelli-Olpin and Tyler Gillett. Ready or Not is a story of generational wealth, told from the perspective of Grace (Samara Weaving), the new bride of Alex (Mark O’Brien), an estranged member of the Le Domas family. To outsiders like Grace, the Le Domases made their fortune selling board games and owning sports franchises. But after the wedding, she discovers that their riches come not from ingenuity or hard work, but from a literal deal with the devil. In the 19th century, a Le Domas patriarch accepted a challenge from a Satanic figure called Mr. Le Bail: if the patriarch solves a puzzle put before him, Le Bail will finance any operation the patriarch chooses. The puzzle is solved and the Le Domases become billionaires, with one stipulation: every time a new person enters the family, they must all play a randomly selected game.

For her turn, Grace is assigned “hide and seek,” but it’s not the usual playground distraction. Instead, the Le Domases seek the hidden Grace to capture her and sacrifice her to Le Bail, forcing her to fight back against the rich people who would rather kill their son’s wife than lose their privilege.

With its mix of comedy and gore, Ready or Not crystalizes why rich people make the best movie monsters. Mythical creatures like Dracula and super-killers like Jason can provide momentary jolts, but they’re easy to shoo away. “They aren’t real,” we can tell ourselves; “They’re just hideous beasts conjured up by directors and special effects artists.” But the Le Domas family is just as real as Jeff Bezos or Mark Zuckerberg. They don’t walk around with fangs or twisted faces, but with smiles and appeals to civility. They claim to provide a service to us regular folks, and they insist on a right to their billions based on their hard work.

But in the same way that Bezos and Zuckerberg amass millions for themselves while stifling almost everybody else, the Le Domases will kill anyone who gets in the way of their fortune. For all of the compliments Alex’s parents, Tony (Henry Czerny) and Becky (Andie McDowell), lavished on Grace, they have no qualms about killing her to save the status quo. Without exception, the Le Domases sacrifice their servants and even one another to preserve their fortune and the illusion of decency that upholds it.

At the same time, Ready or Not provides a reminder that we all need. Whether the monster is Godzilla, Michael Myers, or the white supremacists of Get Out, nearly every horror movie fundamentally is a story about how evil can be defeated. Even if the threat returns in sequel after sequel, most individual entries follow a hero who refuses to give in to their terror, who sees that the evil opposing them is not omnipotent, who recognizes that the losses they’ve sustained need not consume them, and who overcomes. As much as they exist to scare us, horror movies also work to help us visualize our fears, to give a face to our unspoken anxieties and help us deal with them. As a child, that meant reminding myself that Chucky could be stopped if you threw him a fire. As an adult, that means reminding myself that the rich may have power, but it is not ultimate. We can fight on.

Ready or Not shouts this reminder throughout its breezy 94-minute runtime. It places the Le Domas family within the tradition of great movie monsters, grounding them in the terrors capitalism imposes on us all, but it shows us that the beast can be defeated. We will likely end up like Grace at the end of the film, battered and bathed in blood, emotionally scarred from the false friendships she had to shed, but ultimately clear-eyed. With that perspective, we celebrate in Grace’s exhausted but triumphant walk from the Le Domas mansion, where she sits on the steps as the building burns behind her and indulges in a calming cigarette.

That image is the one horror movie scene I’m happy to dream about.

Joe George writes about movies, comics, and tv for Tor.com, Bloody Disgusting, and Think Christian. He collects his work at joewriteswords.com and tweets nonsense from @jageorgeii.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.